![Prolonged Fever in Pediatric Patients]()

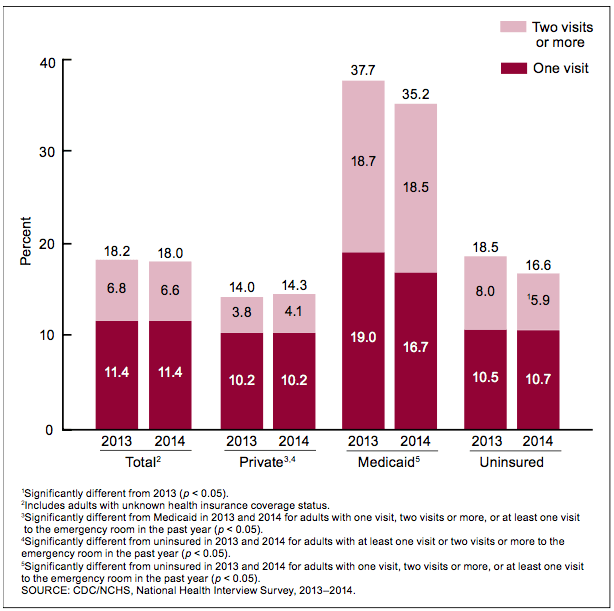

Febrile pediatric patients are ubiquitous in emergency departments (ED) around the country. Parents agonize over the presence, height, and persistence of fever, despite the energy we invest in attempting to reassure them and minimize ‘fever phobia’. But when should we, as providers, also be worried? Very often in pediatric patients we are trying to distinguish self-limited viral infections from potentially harmful bacterial ones. In ill-appearing patients, it’s easy. We treat the patient aggressively as if their symptoms were attributable to a bacterial infection. The proper approach is more opaque with the relatively well-appearing febrile child. How do we pick out the bacterial infections in these cases?

Part of the answer to this question is determined by the patient’s age.

The Neonate

The evaluation of a neonate with fever is straightforward, in some ways the simplest. We assume the patient has a bacterial infection until proven otherwise. We routinely obtain blood, urine, and spinal fluid for analysis and culture, consider chest X-ray and stool cultures, and treat empirically with antibiotics until the cultures are negative. Neonates can certainly be ill and at times represent challenging resuscitation scenarios, but the evaluation and management of a febrile-but-otherwise-well-appearing neonate is not, cognitively speaking, a particularly complex enterprise.

Infants (29 days-3 months old)

These infants are only slightly more complicated. There exists some institutional variability, but in most settings, all patients will have urine and blood obtained to risk stratify. The practitioner should strongly consider a lumbar puncture given the limitations of the physical exam (this latter point is the subject of much debate). Depending on the patient’s risk category, the care team may admit and/or treat with antibiotics or discharge home with close follow-up..

Children (>3 months old)

Due to the successes of widespread immunization in this country, particularly Haemophilus influenza type B and Streptococcus pneumoniae, febrile children older than 3 months are often considered to be low risk for serious bacterial infection and are given a summary treatment in many fever reviews. We are frequently reminded that the rates of occult bacteremia in the post-PCV7 and Hib era have dropped dramatically, from 5% in highly febrile children to <1-2% in the modern era [1] [2][3][4]. We are therefore implored not to routinely obtain blood cultures and complete blood counts on otherwise healthy, generally well-appearing febrile children. These tests are not usually helpful and frequently lead to false positives that magnify patient and parental anxiety, and burden the health system in the form of repeat visits and additional costs. It is easy enough to abstain from ordering blood cultures and CBCs. But who, among these well appearing patients, should we worry about? Certainly a few among these well appearing patients will have serious pathology. How do we pick them out? That is why, in my opinion, these patients constitute perhaps the most challenging age group in determining appropriate diagnostic work-up and management.

How aggressively should I work-up a child with 5 days of fever, rhinorrhea, and congestion? What if that patient had a cough but their lungs were clear? What if they were wheezing? What if their rapid flu was positive? Let’s consider a few cases that you almost certainly have seen in your ED.

Case 1

A 4-year-old boy presents with 5 days of fever, congestion, occasional non-bloody, non-bilious emesis, and some loose stools. His 16 month-old sister starting getting sick yesterday with similar symptoms. His vital signs are: T 39.5C, HR 125, RR 22, BP 98/67. His oxygen saturation is 100% on room air. He is tired-appearing but non-toxic. Tympanic membranes look normal and his oropharynx is only mildly erythematous. His lungs are clear to auscultation bilaterally. Abdomen is soft, non-tender, and there is no rash. It’s February, and you think he might have the flu. So you order a rapid flu. Eureka! It’s positive. You inform the family and neatly invoke this as the explanation for their child’s fever. The mother, however, is not reassured. She says “I’m worried about this fever. Are you sure it’s just the flu? How long is the fever going to last?”

How long does the fever from common viral illnesses last?

The answer is, not surprisingly, dependent on the virus. An old, but very informative study published in the American Journal of Disease of Children studied children aged 3 months to 15 years diagnosed with influenza A and B, parainfluenza 1, 2, and 3, RSV, and adenovirus, evaluating both duration and height of fever [5]. The following table summarizes their findings.

![Screen Shot 2016-04-25 at 8.21.32 PM]()

Note, the average duration of fever for influenza A and B is >5 days. Parainfluenza 2 had the shortest duration, at 2.5 days, with the rest of the evaluated viruses having an intermediate duration.

Can a bacterial co-infection exist with influenza?

In a study of patients hospitalized with influenza from 2003-10, 2% were found to have culture-positive bacterial infections, most commonly Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus. Of note, this almost certainly underestimates the true incidence of bacterial coinfection, given that bacterial cultures were collected at the discretion of treating physicians rather than in a systematic fashion. Additionally, pneumonia complicated influenza in 25% of these patients, many of which likely represented bacterial-viral coinfection not detected by blood or sputum culture [6]. Additionally, influenza alone can be serious business, with complications including encephalopathy, rhabdomyolysis, acute kidney injury, and myocarditis. So viral respiratory infections can have serious sequelae. However, in the relatively well appearing child with fever of 5 days duration, we needn’t necessarily invoke an alternative explanation for fever. Influenza can certainly cause fever of this duration, and in fact typically does.

Case 1 Answer

So yes, concerned parent, the virus can certainly cause fever of this duration. Continue to use antipyretics as needed to keep your child comfortable, watch for worsening symptoms, and follow-up closely with your primary care doctor.

Speaking of lower respiratory tract infections, what about pneumonia? How reliable is my exam for picking it out, and do I need to worry about “occult pneumonia”?

Case 2

You are seeing a 3-year-old girl with runny nose, cough, and fever up to 39.0C at home, for about 5 days. The patient has been seen by her primary care physician and was diagnosed with a viral upper respiratory infection (URI). With persistent symptoms, her parents bring to the ED. She is comfortable, but apprehensive to exam. Vital signs are temp 38.4C, HR 116, RR 24 (99% on room air), and BP 92/66. She has no evidence of acute otitis media, her lungs are clear, and she has easy work of breathing. You obtain a rapid flu, and it’s negative. Her parents say, “Geez doc, she sure is coughing a lot, especially at night. Could she have pneumonia?” As illustrated by the previous study, this may simply be a respiratory virus. But are you sure this child does NOT have pneumonia? And if you’re not, should you get a chest X-ray?

When should you get a chest X-ray for pneumonia?

In a febrile child with respiratory distress or adventitious sounds to auscultation of the chest, the decision to obtain a chest X-ray is somewhat straightforward (a caveat, of course, for young infants who have clinical bronchiolitis, in which case a radiograph is NOT routinely warranted). In children with a fever, cough, and clear lungs, the decision is much less clear. Multiple studies have demonstrated that some percentage of febrile pediatric patients without respiratory distress or abnormal auscultatory findings will have radiographic pneumonia. In the pre-heptavalent pneumococcal vaccine (PCV-7) era, the incidence of so-called “occult pneumonia” was estimated to be from 15-25% [7][8]. Recent studies in the post-pneumococcal vaccine era suggest that occult pneumonia is present in 5-9% of febrile pediatric patients without clinical findings of pneumonia [8][9].

Here is the diagnostic challenge: If these patients have no clinical findings of pneumonia, how do we pick them out? A 2010 study attempted to answer this question [10]. Of 308 eligible patients, 21 (6.8%) had occult pneumonia (i.e. no signs of respiratory distress and no lower respiratory tract findings on exam). The authors considered a variety of potential predictive factors to identify occult pneumonia, including duration of fever, presence and duration of cough, height of temperature, oxygen saturation, and serum WBC count, among others. Unfortunately, the authors could find no strong predictors for the presence of occult pneumonia. They did find that fevers >1 day and worsening cough were moderately predictive.

Figure 1. Decision tree for the identification of patients with occult pneumonia; for this analysis, patients with equivocal chest radiographs are considered to have pneumonia [10]

![Screen Shot 2016-04-29 at 5.13.26 PM]()

What about the 2-year-old child with truly prolonged fever?

What about the patient chart with a chief complaint of “fever, congestion x 2 months”? Often, a careful history will elucidate a more multiphasic illness course that constitutes consecutive viral or minor bacterial infections. As Dr. Gary Marshall succinctly puts it, “Kids get sick all the time.” [11] In fact, an old but excellent study examining children attending daycare found that the average child aged 6 weeks to 5 years suffered 6.5 respiratory illnesses per year, with a peak rate of 10.4 illnesses per year at age 6 months to 1 year. Sick all the time indeed. I’ve found that normalizing the frequency of respiratory illnesses in young children can to some degree assuage parental anxiety about recurrent URIs and fevers. But what about situations where an illness seems to be legitimately prolonged and discrete?

Case 3

You are seeing a 2-year-old boy with congestion, cough, and fever, up to 102F at home, for 10 days. His parents state that they have been seen 3 times by their primary care physician and have been reassured that this is a “common cold”. Parents report his symptoms are getting worse. The patient is non-toxic on exam, but clings to his mother. Vital signs are temp 39.1C, HR 122, RR 24 (100% room air), and BP 91/66. He has no evidence of acute otitis media but has copious mucopurulent nasal discharge. His lungs are clear, and he has easy work of breathing. A chest X-ray is normal. His parents say, “He’s never been sick this long, doc; he can’t breathe out of his nose and he is coughing a lot. Is there anything we can do to make him get better faster?” You try to remember, do little kids get sinusitis?

Sinusitis in kids

According to the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), they can indeed get sinusitis. Though the frontal and sphenoid sinuses pneumatize over a period of years, the ethmoid and maxillary sinuses are present at birth, with the latter rapidly expanding by 4 years of age. Though acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS) is less common in children <2 years old, it occurs frequently in pediatric patients aged 4-7 years and is observed even in infants. One 2010 study using strict inclusion criteria found that compared to those receiving placebo, children aged 1-10 years who received amoxicillin/clavulanic acid were more likely to be ‘cured’ (50% vs 14%) and less likely to have treatment failure (14% vs 68%) [13]. So appropriate antibiotic therapy can expedite recovery and mitigate symptoms in children with ABRS.

The operative phrase here, however, is “strict inclusion criteria”. Every child who presents with mucoid rhinorrhea and a tactile fever does NOT need antibiotics, and in fact will not benefit from antimicrobial treatment. Also consider the side effects of antibiotic therapy (diarrhea, rash, antibiotic resistant microbes). The presumptive diagnosis of ABRS should be made when a child with URI symptoms meets 1 of the following 3 conditions [12]:

- Persistent illness (nasal discharge or daytime cough or both lasting >10 days without improvement)

- Worsening course (worsening or new onset of nasal discharge, daytime cough, or fever after initial improvement)

- Severe onset (concurrent fever with temperature ≥39°C/102.2°F and purulent nasal discharge for ≥3 consecutive days)

If the child does not meet these criteria, antibiotics should not be prescribed. If they meet criteria for worsening or severe symptoms, antibiotics should likely be employed, and if symptoms are persistent, they should at least be considered. So for the child in our case, with 10 days of worsening symptoms, fevers, and purulent nasal discharge, in discussion with parents, I would likely treat with antimicrobials.

Prolonged Fever in Pediatric Patients: Final Points

None of the patients described above were exceptionally ill. Likely these will represent a large portion of the pediatric patients you will see in daily practice. Fever is very often a manifestation of a self-limited viral illness in the otherwise healthy pediatric patient: the hard part is deciding when it is not. Though this discussion has only scratched the surface, hopefully it serves to highlight some of the nuanced decisions that must be made when approaching the febrile pediatric patient.

References

- Carstairs K, Tanen D, Johnson A, Kailes S, Riffenburgh R. Pneumococcal bacteremia in febrile infants presenting to the emergency department before and after the introduction of the heptavalent pneumococcal vaccine. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(6):772-777. PMID: 17337092

- Herz A, Greenhow T, Alcantara J, et al. Changing epidemiology of outpatient bacteremia in 3- to 36-month-old children after the introduction of the heptavalent-conjugated pneumococcal vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(4):293-300. PMID: 16567979

- McGowan J, Bratton L, Klein J, Finland M. Bacteremia in febrile children seen in a “walk-in” pediatric clinic. N Engl J Med. 1973;288(25):1309-1312. PMID: 4145198

- Teele D, Pelton S, Grant M, et al. Bacteremia in febrile children under 2 years of age: results of cultures of blood of 600 consecutive febrile children seen in a “walk-in” clinic. J Pediatr. 1975;87(2):227-230. PMID: 1151561

- Putto A, Ruuskanen O, Meurman O. Fever in respiratory virus infections. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140(11):1159-1163. PMID: 3020965

- Dawood F, Chaves S, Pérez A, et al. Complications and associated bacterial coinfections among children hospitalized with seasonal or pandemic influenza, United States, 2003-2010. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(5):686-694. PMID: 23986545

- Bachur R, Perry H, Harper M. Occult pneumonias: empiric chest radiographs in febrile children with leukocytosis. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(2):166-173. PMID: 9922412

- Murphy C, van de, Harper M, Bachur R. Clinical predictors of occult pneumonia in the febrile child. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(3):243-249. PMID: 17242382

- Rutman M, Bachur R, Harper M. Radiographic pneumonia in young, highly febrile children with leukocytosis before and after universal conjugate pneumococcal vaccination. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25(1):1-7. PMID: 19116501

- Shah S, Mathews B, Neuman M, Bachur R. Detection of occult pneumonia in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(9):615-621. PMID: 20805779

- Marshall G. Prolonged and recurrent fevers in children. J Infect. 2014;68 Suppl 1:S83-93. PMID: 24120354

- Denny F, Collier A, Henderson F. Acute respiratory infections in day care. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8(4):527-532. PMID: 3529308

- Chow A, Benninger M, Brook I, et al. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(8):e72-e112. PMID: 22438350

- Wald E, Applegate K, Bordley C, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of acute bacterial sinusitis in children aged 1 to 18 years. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e262-80. PMID: 23796742

- Wald E, Nash D, Eickhoff J. Effectiveness of amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium in the treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis in children. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):9-15. PMID: 19564277

Author information

Assistant Professor

Department of Emergency Medicine

Oregon Health and Science University

The post PEM Pearls: Prolonged Fever in Pediatric Patients – When should you worry? appeared first on ALiEM.

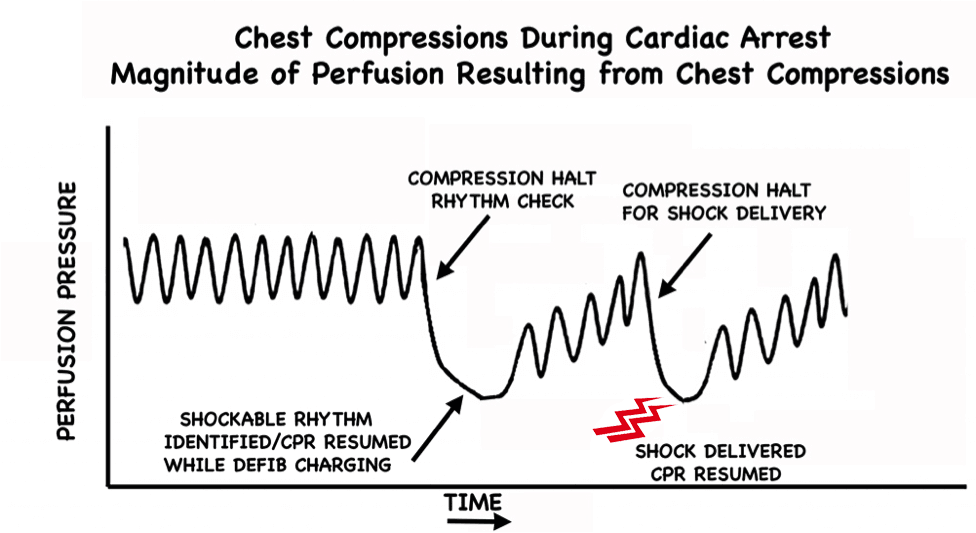

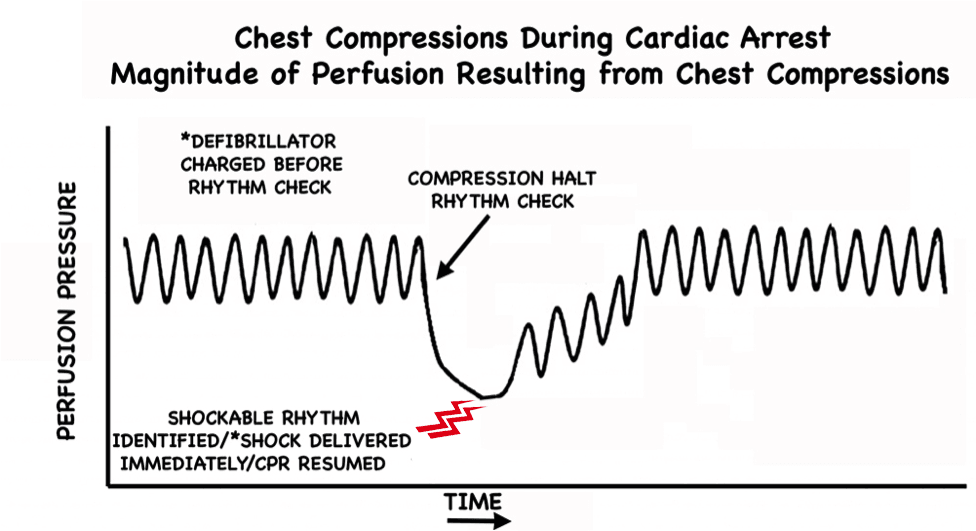

In cardiac arrest care it is well accepted that time to defibrillation is closely correlated with survival and outcome [1]. There has also been a lot of focus over the years on limiting interruptions in chest compressions during CPR. In fact, this concept has become a major focus of the current AHA Guidelines. Why? Because we know interruptions are bad [2,3]. One particular aspect of CPR that has gotten a lot of attention in this regard is the peri-shock period. It has been well established that longer pre- and peri-shock pauses are independently associated with decreased chance of survival [4,5]. Can we do better to shock sooner and minimize these pauses?

In cardiac arrest care it is well accepted that time to defibrillation is closely correlated with survival and outcome [1]. There has also been a lot of focus over the years on limiting interruptions in chest compressions during CPR. In fact, this concept has become a major focus of the current AHA Guidelines. Why? Because we know interruptions are bad [2,3]. One particular aspect of CPR that has gotten a lot of attention in this regard is the peri-shock period. It has been well established that longer pre- and peri-shock pauses are independently associated with decreased chance of survival [4,5]. Can we do better to shock sooner and minimize these pauses?

Pain is the most common reason people seek care in Emergency Departments. In addition to diagnosing the cause of the pain, a major goal of emergency physicians (EPs) is to relieve pain. However, medications that treat pain can have their own set of problems and side effects. The risks of treatment are particularly pronounced in older adults, who are often more sensitive to the sedating effects of medications, and are more prone to side effects such as renal failure. EPs frequently have to find the balance between controlling pain and preventing side effects. Untreated pain has large personal, emotional, and financial costs, and more effective, multi-modal pain management can help reduce the burden that acute and chronic pain place on patients [1]. There is evidence that older adults are less likely to receive pain medication in the ED [2,3]. The first step to improving, is being aware of the potential tendency to under-treat pain in older adults. Here are 5 tips to help you effectively manage pain in older adults on your next shift.

Pain is the most common reason people seek care in Emergency Departments. In addition to diagnosing the cause of the pain, a major goal of emergency physicians (EPs) is to relieve pain. However, medications that treat pain can have their own set of problems and side effects. The risks of treatment are particularly pronounced in older adults, who are often more sensitive to the sedating effects of medications, and are more prone to side effects such as renal failure. EPs frequently have to find the balance between controlling pain and preventing side effects. Untreated pain has large personal, emotional, and financial costs, and more effective, multi-modal pain management can help reduce the burden that acute and chronic pain place on patients [1]. There is evidence that older adults are less likely to receive pain medication in the ED [2,3]. The first step to improving, is being aware of the potential tendency to under-treat pain in older adults. Here are 5 tips to help you effectively manage pain in older adults on your next shift.

, and illustrations were created by Dr. Mary Haas.

, and illustrations were created by Dr. Mary Haas.

Welcome to another ultrasound-based case, part of the “Ultrasound For The Win!” (

Welcome to another ultrasound-based case, part of the “Ultrasound For The Win!” ( Figure 1. Cobblestoning of subcutaneous soft tissue with fluid in the deeper fascial plane.

Figure 1. Cobblestoning of subcutaneous soft tissue with fluid in the deeper fascial plane. Figure 2. Another view of the cobblestoning of subcutaneous soft tissue and fluid in the deep fascial plane.

Figure 2. Another view of the cobblestoning of subcutaneous soft tissue and fluid in the deep fascial plane. Figure 3. Cobblestoning of the subcutaneous tissue (#) and fluid in the deep fascial plane (arrow) is seen.

Figure 3. Cobblestoning of the subcutaneous tissue (#) and fluid in the deep fascial plane (arrow) is seen.

Welcome to the Orthopedics Lower Extremity Module! After carefully reviewing all relevant posts from the top 50 sites of the

Welcome to the Orthopedics Lower Extremity Module! After carefully reviewing all relevant posts from the top 50 sites of the