![Fentanyl]() Drug poisoning is now the leading cause of injury death in the United States [1], with opioids accounting for up to 40% of these deaths. In the U.S., prescription opioid death rates have more than quadrupled since 1999, and death rates exceed those due to motor vehicle crashes [2]. Similar trends in opioid exposure and death rates in Canada suggest that it is not far behind. Prescriptions for opioid analgesics paralleled a rise in opioid abuse and fatalities between 2002 and 2010, leveling off between 2011 and 2013 [3], only to rise again in 2014 [1]. Among the more frequently misused opioids nationwide are oxycodone and hydrocodone (the most widely prescribed drug in the U.S.) in their various formulations, and methadone, but a “rising star” in the epidemic in many regions is fentanyl.

Drug poisoning is now the leading cause of injury death in the United States [1], with opioids accounting for up to 40% of these deaths. In the U.S., prescription opioid death rates have more than quadrupled since 1999, and death rates exceed those due to motor vehicle crashes [2]. Similar trends in opioid exposure and death rates in Canada suggest that it is not far behind. Prescriptions for opioid analgesics paralleled a rise in opioid abuse and fatalities between 2002 and 2010, leveling off between 2011 and 2013 [3], only to rise again in 2014 [1]. Among the more frequently misused opioids nationwide are oxycodone and hydrocodone (the most widely prescribed drug in the U.S.) in their various formulations, and methadone, but a “rising star” in the epidemic in many regions is fentanyl.

In March 2015, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) issued nationwide alerts that identified fentanyl as a significant threat to public health and safety [10]. The National Forensic Laboratory Information System report a more than 8-fold increase in the total number of fentanyl seizures between 2012 and 2014 [11]. Additionally, in late 2013 and 2014, the DEA National Heroin Threat Assessment Summary noted spikes in overdose deaths related to fentanyl and its analog, acetyl-fentanyl, throughout the U.S. [12].

What is fentanyl? Is it any worse than other opioids?

Fentanyl is a commonly used medication in Emergency Departments (EDs) and inpatient units throughout Canada and the U.S. It is effective for pain control when used appropriately and is about 100 times more potent than morphine and 30-50 times more potent than heroin. Fentanyl is a schedule I drug by the Canadian Controlled Drugs and Substances Act and schedule II by the U.S. Controlled Substances Act. This scheduling reinforces that although fentanyl has currently accepted medical uses, it carries a high potential for abuse and may lead to severe psychological or physical dependence.

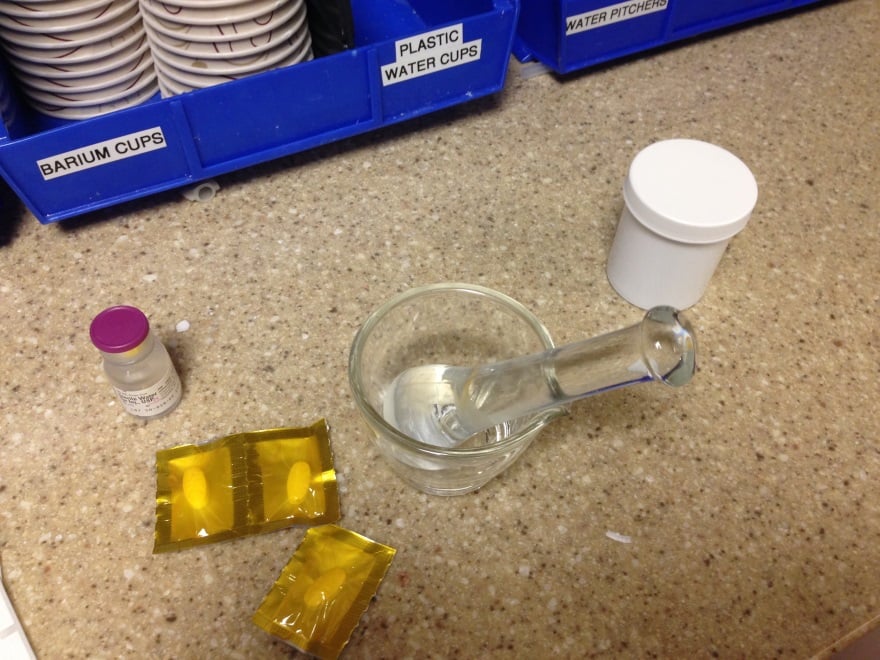

Pharmaceutical fentanyl is available in injectable solutions (intravenous and intramuscular), transdermal patches, sublingual sprays, transmucosal lozenges, transbuccal tablets, and intranasal sprays. Access to pharmaceutical fentanyl for the purpose of abuse occurs primarily through diversion or theft of prescribed fentanyl in transdermal formulation.

However, since much of the fentanyl now available for abuse is illicitly manufactured, it is referred to as non-pharmaceutical fentanyl (NPF). Although large-scale, epidemic fentanyl and fentanyl analog (i.e. acetyl-fentanyl, α-methylfentanyl) poisoning is relatively new, small outbreaks have occurred numerous times in the U.S. over the past 25 years [4][5][6][7][8][9]. Testing of drug samples is able to differentiate between pharmaceutical grade fentanyl and NPF, and the majority of the >700 fentanyl-related overdose deaths during this time were attributed to NPF [11].

Fentanyl powder is highly concentrated and requires dilution before it is combined with other street drugs, including heroin, or pressed into pills and sold on the streets. Common routes of exposure include intravenous, oral, and insufflation. Despite the poor oral bioavailability of fentanyl, it is easy to administer sufficient amounts of drug to allow absorption of sufficient amounts to cause euphoria, as well as respiratory depression and death. The amount of drug, and even the specific content of the product being used (e.g., could it be a fentanyl analog) is essentially unknowable by the consumer. Combined with the extreme potency of fentanyl and its derivatives (some 10,000 times that of morphine), the risk of overdose is extremely high.

How and where is NPF being produced? How is NPF used?

NPF and fentanyl analogs are produced in clandestine laboratories through relatively simple chemical processes that can be found online. Most commonly, NPF is produced via the Siegfried method that uses N-phenethyl-piperidone as a precursor. In 2006, in response to rising numbers of NPF-related deaths, the CDC implemented an ad-hoc case finding and surveillance system that identified 1,013 NPF-related deaths between April 4, 2005 and March 28, 2007. The production of NPF was related to clandestine production in a laboratory in Toluca, Mexico, as well as domestic production within the U.S. [13] As a result, in 2007 the DEA began regulating access to N-phenethyl-piperidone [14].

Currently, clandestinely-produced fentanyl is primarily sourced from Mexico; fentanyl analogs and precursor chemicals are obtained from distributors in other countries including China, Germany, and Japan [10]. Pharmaceutical fentanyl is also diverted for abuse, but at much lower levels. There have also been several clandestine laboratories identified in Canada by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), however, much of the NPF is produced in other countries, predominantly China, then imported to Canada.

Of note, on October 1, 2015, the Chinese Ministry of Public Security (MPS) Narcotics Control Bureau announced the regulation of the sale and distribution of 116 chemical compounds used in the production of synthetic drugs, including acetyl-fentanyl. Chinese officials declared these compounds were found to have no known legitimate use and therefore will be controlled administratively by the MPS.

What is the epidemiology of fentanyl use in North America?

Over the past several years, many provinces across Canada, including Alberta, have seen a significant increase in exposures and deaths related to fentanyl and fentanyl analog exposure. Illicit NPF was first identified in Montreal, Quebec in May 2013, and the Canadian Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (CCENDU) correctly predicted that the availability of NPF was likely to spread throughout Canada to other regions. CCENDU report 1,019 drug poisoning deaths between 2009 and 2014 in whom post-mortem toxicology analysis identified fentanyl.

Since June 2013, the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse (CCSA) has reported the availability of NPF in pill and powder form across Canada that is being sold on the street as “green monsters”, “green beans”, “green jellies”, or “street oxy”. It is often sold to users who believe they are receiving oxycodone, heroin, or other drugs of abuse including stimulant drugs such as MDMA (“ecstasy”) and cocaine [15]. In fact, many pills being sold as counterfeit oxycodone are made to resemble Oxycontin® or Roxicodone, with identical markings and colors, prompting stricter regulation over the purchase and use of pill-forming machines. Health Canada’s Drug Analysis Service has identified fentanyl in 89% of samples of seized counterfeit oxycodone tablets, and overall seizures of fentanyl, including both diverted prescription grade and NPF, increased over 30 times between 2009 and 2014 [16].

NPF drug seizures and deaths have had a similar progress across the U.S., particularly the eastern half [11]. Rhode Island experienced 12 deaths in 2013 from acetylfentanyl [8].

In the St. Louis area, fentanyl alone was the primary death factor in 44% of fentanyl-related overdose cases while the remaining 56% involved fentanyl along with other substances such as alcohol, pharmaceuticals, cocaine, or heroin.

In Alberta specifically, with a population of roughly 4 million, there were 162 fentanyl-detected deaths (including all deaths for which post-mortem toxicological testing detected the presence of fentanyl) and 61 fentanyl-implicated deaths (where fentanyl was identified as the direct cause or a contributing cause of death) between 2011 and 2014 [16]. The scope of the epidemic is so great that Alberta’s health authority has formed an ad hoc emergency command center, previously reserved for infectious disease outbreaks such as measles or H1N1, to coordinate efforts against the rising public health threat.

In July 2015, the DEA New Jersey Tactical Diversion Squad identified an illicit organization that was distributing counterfeit Roxicodone pills that were in fact 40% acetyl-fentanyl. Subsequent testing of similar Roxicodone pills from the same organization in December 2015 revealed that the pills now contained 60% pharmaceutical grade fentanyl-citrate. Not surprisingly, many chronic opioid abusers who present with unintentional fentanyl overdoses believed they were purchasing oxycodone or another drug of abuse, and the significantly different potency and pharmacokinetics of fentanyl contributed to opioid toxicity. However, not all fentanyl use occurs in chronic opioid users, and many overdoses occur in opioid-naïve users under the age of 40 [17].

![Map canstockphoto3179047]()

What are the challenges in tracking the fentanyl epidemic?

Several limitations regarding exposure and death reporting make estimating the overall burden on society difficult. First, many patients with fentanyl exposures who present to the ED are unidentified as such (i.e., fentanyl cannot be detected by a hospital laboratory; it is very hard to detect the analogues even in a reference laboratory) and remain unreported to the regional poison control centers and health departments, leading to underrepresentation of the incidence of exposures. Without accurate history from family or friends, these cases may not be appreciated as fentanyl related. The medical examiner/coroners suffer the same limitations.

The commonly accepted response to naloxone as diagnostic of an opioid overdose may not occur in patients with late presentations to healthcare following fentanyl exposure since they have already developed sequelae of prolonged hypoxic injury (this is true for all opioids). However, it is especially concerning with fentanyl, given its high potency and the ease in which a profound overdose can occur. Also, drug poisoning death reporting and certification varies across regions throughout North America. Furthermore, although in the U.S. the National Center for Health Statistics tracks fentanyl-related deaths through the use of death certificates, a national surveillance system is currently lacking in Canada. The Statistics Canada Vital Statistics Death Database offers a potential source for estimating opioid related deaths, however its utility relies on accurate coding of patient presentations using International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10), which, as noted, is limited by the ability to make the clinical diagnosis [18].

![]()

What is the treatment for patients with fentanyl overdose?

Naloxone is a competitive opioid antagonist, capable of reversing the effects of fentanyl and other opioid agonists. Patients in the ED with respiratory depression from suspected opioid toxicity, who are not intubated, are candidates for the administration of naloxone. The starting IV dose is 0.04 mg, and this is titrated to effect [19]. Most patients with opioid-induced respiratory depression will respond to small doses of naloxone [20][21]; however, anecdotally, some report that patients with fentanyl poisoning have required very high doses of fentanyl (up to 12 mg) to reverse opioid effects [9]. Because there is no pharmacologic or clinical reason to explain this requirement, it may be due to the use of a fentanyl analog (with high binding affinity for the mu receptor), another concomitant sedative, hypoxia, or a nonspecific effect.

Naloxone administration is predominantly done by trained health care providers, including ED physicians and EMS personnel. Given the rapid and potent effects of fentanyl, significant hypoxia and end organ effects may occur by the time EMS is activated; the ability to administer an opioid antagonist early after overdose offers significant potential benefits to morbidity and mortality.

Take-home naloxone programs

Take-home naloxone programs have been working to deliver naloxone training to high-risk inpatients, ED patients, and outpatients seen in clinic, as well as to friends and family who may be present during an opioid overdose [14]. These programs first appeared in the U.S. in 1996 and have continued to grow and expand, with 9 states passing laws to expand access to naloxone in early 2015, taking the total number of jurisdictions with naloxone access laws to 37 as of July 2015 [22][23]. Programs are sprouting up across Canada as well. A survey from the Harm Reduction Coalition assessed organizations in the US distributing naloxone kits between 1996 and June 2014 and found that 152,283 kits were distributed with reports of 26,463 administrations [22].

In addition to these community-based distribution programs for take home naloxone, New York City has now made naloxone available for purchase over the counter, further increasing availability of the potentially life saving antidote. Others are following this trend, and Health Canada has made similar proposals to allow access to naloxone without a prescription.

What does the future hold?

The fentanyl epidemic across Canada and the U.S. is a significant threat to public health. The development of this epidemic has paralleled that of heroin, and it may be that a similar demographic of former prescription opioid users are at greatest risk [24][25]. The meteoric rise in use and consequence shows no current signs of slowing and reinforces the need for improved methods for identification and reporting of fentanyl exposures and deaths. In the background of the fentanyl epidemic are a new class of ultrapotent opioids called the research chemical (RC) opioids. Drugs such as W-18 have potencies that dwarf those of the fentanyls and are very difficult to detect analytically. We hope that through public education, intelligence, and law enforcement efforts, the expanded use of take-home naloxone, and support of addiction services will help to curb the use and deaths from of fentanyl abuse.

References

- Warner M, Chen LH, Makuc DM, Anderson RN, et al. Drug poisoning deaths in the United States, 1980-2008. NCHS Data Brief 2011 (81):1-8. ▲

- Chen LH, Hedegaard H, Warner M. Drug-poisoning Deaths Involving Opioid Analgesics: United States, 1999-2011. NCHS Data Brief 2014 (166):1-8. ▲

- Dart RC, Severtson SG, Bucher-Bartelson B. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372(16): 1573-4. PMID: 25875268 ▲

- Martin M, Hecker J, Clark R, et al. China White epidemic: an eastern United States emergency department experience. Ann Emerg Med. 1991; 20(2): 158-64. PMID: 1996799 ▲

- Hibbs J, Perper J, Winek CL. An outbreak of designer drug–related deaths in Pennsylvania. JAMA. 1991; 265(8): 1011-3. PMID: 1867667 ▲

- Acetyl fentanyl overdose fatalities–Rhode Island, March-May 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013;62(34):703-4. ▲

- Algren DA, Monteilh CP, Punja M, et al. Fentanyl-associated fatalities among illicit drug users in Wayne County, Michigan (July 2005-May 2006). J Med Toxicol. 2013; 9(1): 106-15. PMID: 23359211 ▲

- Mercado-Crespo MC, Sumner SA, Spelke MB, Sugerman DE, et al. Notes from the field: increase in fentanyl-related overdose deaths – Rhode Island, November 2013-March 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63(24):531. ▲ ▲

- Schumann H, Erickson T, Thompson TM, Zautcke JL, Denton JS. Fentanyl epidemic in Chicago, Illinois and surrounding Cook County. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2008; 46(6): 501-6. PMID: 18584361 ▲

- US Drug Enforcement Administration. DEA Issues Nationwide Alert on Fentanyl as Threat to Health and Public Safety. March 2015. Accessed December 15, 2015. ▲▲

- CDC Health Alert Network. Increases in Fentanyl Drug Confiscations and Fentanyl-related Overdose Fatalities. October 2015. Accessed December 15, 2015. ▲▲▲

- US Drug Enforcement Administration Intelligence Report. National Heroin Threat Assessment Summary (PDF). April 2015. Accessed December 15, 2015. ▲

- US Drug Enforcement Administration. Control of a Chemical Precursor Used in the Illicit Manufacture of Fentanyl as a List I Chemical. April 2007. Accessed January 4, 2015. ▲

- Nonpharmaceutical fentanyl-related deaths–multiple states, April 2005-March 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008;57(29):793-6. ▲▲

- CCENDU Drug Alert: Illicit Fentanyl (PDF). 2013. Accessed October 25, 2015. ▲

- CCENDU Bulletin: Deaths Involving Fentanyl in Canada, 2009-2014 (PDF). 2015. Accessed October 25, 2015. ▲▲▲

- CCENDU Drug Alert: Fentanyl-related Overdoses (PDF). 2015. Accessed October 25, 2015. ▲

- Gladstone E, Smolina K, Morgan SG, Fernandes KA, Martins D, Gomes T. Sensitivity and specificity of administrative mortality data for identifying prescription opioid-related deaths. CMAJ. 2015. PMID: 26622006 ▲Kim HK, Nelson LS. Reversal of Opioid-Induced Ventilatory Depression Using Low-Dose Naloxone (0.04 mg): a Case Series. J Med Toxicol. 2015. PMID: 26289651 ▲

- Takahashi M, Sugiyama K, Hori M, Chiba S, Kusaka K. Naloxone reversal of opioid anesthesia revisited: clinical evaluation and plasma concentration analysis of continuous naloxone infusion after anesthesia with high-dose fentanyl. J Anesth. 2004; 18(1): 1-8. PMID: 14991468 ▲

- Tigerstedt I Reversal of fentanyl-induced narcotic depression with naloxone following general anaesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1978; 22(3): 234-40. PMID: 676644 ▲

- Wheeler E, Jones TS, Gilbert MK, Davidson PJ. Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs Providing Naloxone to Laypersons – United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64(23):631-5. ▲▲

- Naloxone overdose prevention laws. Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System (July 2015). Accessed December 5, 2015. ▲

- Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Harney J. Shifting Patterns of Prescription Opioid and Heroin Abuse in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373(18): 1789-90. PMID: 26510045 ▲

- Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between Nonmedical Prescription-Opioid Use and Heroin Use. N Engl J Med. 2016; 374(2): 154-63. PMID: 26760086 ▲

- Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths – United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;64(50-51):1378–82. ▲

Further Reading:

Images: Naloxone, Map (c) Can Stock Photo

Author information

Emergency physician, Medical Toxicologist

Department of Emergency Medicine

University of Calgary, Alberta Health Services

Poison and Drug Information Service (PADIS)

The post Fentanyl: Adding Fuel to the Fire in the North American Opioid Epidemic appeared first on ALiEM.

following questions:

following questions:

Older adults are at high risk of poor outcomes from even minor head injuries. We see many older patients in the ED who present after a fall or head injury, and we have good decision rules for which patients need brain imaging

Older adults are at high risk of poor outcomes from even minor head injuries. We see many older patients in the ED who present after a fall or head injury, and we have good decision rules for which patients need brain imaging

There are many pitfalls the practicing Emergency Medicine practitioner can encounter, but hopefully avoid during their time in the ED. Bounceback patients, the ones who come back the next day, usually worse off than the day before, are definitely dreaded events that most would like to avoid. Of course, the ideal goal would be to never have that happen to you or your patients, but that is just not realistic. That’s why Bouncebacks! can be integral to anyone’s reading list.

There are many pitfalls the practicing Emergency Medicine practitioner can encounter, but hopefully avoid during their time in the ED. Bounceback patients, the ones who come back the next day, usually worse off than the day before, are definitely dreaded events that most would like to avoid. Of course, the ideal goal would be to never have that happen to you or your patients, but that is just not realistic. That’s why Bouncebacks! can be integral to anyone’s reading list.

Get ready for another round of 60-Second Soapbox! Each episode, one lucky individual gets exactly 1 minute to present their rant-of-choice to the world. Any topic is on the table – clinical, academic, economic, or whatever else may interest an EM-centric audience. We carefully remix your audio to add an extra splash of drama and excitement. Even more exciting, participants get to challenge 3 of their peers to stand on a soapbox of their own!

Get ready for another round of 60-Second Soapbox! Each episode, one lucky individual gets exactly 1 minute to present their rant-of-choice to the world. Any topic is on the table – clinical, academic, economic, or whatever else may interest an EM-centric audience. We carefully remix your audio to add an extra splash of drama and excitement. Even more exciting, participants get to challenge 3 of their peers to stand on a soapbox of their own!

Welcome to the first Neurology Module! After carefully reviewing all relevant posts from the top 50 sites of the

Welcome to the first Neurology Module! After carefully reviewing all relevant posts from the top 50 sites of the

We are proud to present CAPSULES module 6:

We are proud to present CAPSULES module 6:

Welcome to another ultrasound-based case, part of the “Ultrasound For The Win!” (

Welcome to another ultrasound-based case, part of the “Ultrasound For The Win!” ( Figure 1. Electrocardiogram (ECG) shows T wave inversions in V3-V6. No previous ECG for comparison

Figure 1. Electrocardiogram (ECG) shows T wave inversions in V3-V6. No previous ECG for comparison Figure 2. Parasternal long axis (PSLA) view demonstrating severely depressed ejection fraction

Figure 2. Parasternal long axis (PSLA) view demonstrating severely depressed ejection fraction Figure 3. Parasternal short axis (PSSA) view demonstrating severely depressed ejection fraction

Figure 3. Parasternal short axis (PSSA) view demonstrating severely depressed ejection fraction Figure 4. E-point septal separation (EPSS) of a normal patient in M-mode. EPSS is normal (< 0.7 cm)

Figure 4. E-point septal separation (EPSS) of a normal patient in M-mode. EPSS is normal (< 0.7 cm)